What Does a Tenuta-Coached Irish Defense Look Like?

The beginning of Fall practice marks the end of a long off-season for Notre Dame football.

After limping through the second half of the 2008 campaign, questions surfaced about head coach Charlie Weis’ job security. Despite this, the Irish coaching staff hauled in a solid—albeit not great—recruiting class, and subsequently underwent several coaching changes.

If the Hawaii Bowl is any indication, the offensive woes of the last two years are a thing of the past and the 2009 season will be marked by an aerial assault as quarterback Jimmy Clausen throws to arguably the best wide receiver tandem in the country. Moreover, with defensive coordinator Jon Tenuta calling plays, the Irish defense should feast on a slate of inexperienced quarterbacks. In other words, the Irish defense should be more Hawaii and less regular season.

But the Hawaii Bowl is only one data point that doesn’t, or at least shouldn’t, overshadow an underwhelming 2008 season.

Through the final seven games the Irish offense turned in several disappointing performances, particularly in the second half against North Carolina and through four quarters against Boston College, Syracuse and USC. There were plenty of early warning signs—the Tar Heels merely exposed them—and the remaining Irish opponents followed Butch Davis’ blueprint to success.

Notre Dame’s problems on offense have been discussed ad nauseum this off-season. Play-calling and zone blocking schemes have both been blamed for the primary concern heading into the 2009 season—the running game. While the Irish offense made great strides protecting the passer, improved production on the ground is requisite for Weis’ offense to return to 2005 production levels.

This oft maligned and underachieving unit largely overshadowed the defense. While the defense played fairly well last year, the amount of blitzing should have produced more sacks. When Tenuta was hired it was widely believed he would bring a fierce, attacking defense that would pressure opposing quarterbacks and thwart spread offenses. Save the Hawaii Bowl, this was largely untrue.

So what does a Tenuta-coached Irish defense look like and why wasn’t it consistently on display in 2008? Furthermore, what must Notre Dame do to increase sack production in 2009?

Let’s Talk A Little X’s And O’s

Before answering the questions above, a discussion of defensive scheme is warranted.

First, Tenuta believes in pressure as a philosophy, not something to change the pace of the game or keep opposing offenses from getting into a rhythm. He believes in playing on the opposite side of the line of scrimmage, not letting quarterbacks set their feet, and forcing obvious passing down and distance situations, i.e. winning first down. He has an aggressive personality and emphasizes physical play, but not irrespective of the situation and/or opponent. Coupled with tedious preparation, this last skill is what makes him a superb defensive play-caller.

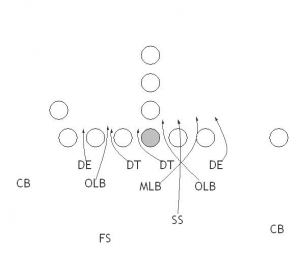

Tenuta’s preferred method of applying pressure is blitzing. As discussed here, blitzing can effectively be broken down into two categories: equal and overload.

An equal blitz scenario occurs when the defense rushes with a number of players equal to—or less than—the number of offensive players in pass protection. Overload blitzing is when the defense rushes the quarterback with more defenders than the offense uses to protect the passer. The latter aims at applying pressure quickly with an unblocked defender, but can lead to uncovered receivers and/or holes in zone coverage.

There are variations to both approaches, but most are focused on disguise and execution. Rolling coverages, dropping defensive linemen into coverage, etc. are mostly window dressing for these two blitz types. One of Tenuta’s specialties is a hybrid of the two.

Rather than rush more defenders than offensive players in pass protection, Tenuta focuses on overloading an area of the field. This overload area blitz attempts to turn a defender loose but doesn’t sacrifice bodies in pass coverage like a traditional overload blitz.

For example, if you take the center as a point of symmetry, an overload area blitz creates favorable defensive numbers on one side of the field. This can make it difficult for the offense to adjust, even if there is an offensive player for every onrushing defender. There are other examples of overloading an area of the defense, but this one will be used for the purposes of this discussion.

The difficulty in executing an area overload blitz lies in three facets: disguise, spacing and coverage.

Disguise

Disguise is surprise and timing, both used to prevent telegraphing a blitz.

Without surprise the defense tips its hand prior to the snap, affording the offense an opportunity to react. The apposite counter to an area overload blitzing scheme is a reallocation of the offensive players assigned to protect the quarterback. The offense can initiate a shift along the offensive line and/or realign tight ends, running backs or receivers to account for the defense’s numbers advantage in the overloaded area.

Additionally, anticipation allows offensive players to take the correct first step. For an athletic, fast defense and aggressive attack like Tenuta’s, this is usually all it takes. Thus, the element of surprise is critical to success.

Timing is coupled with momentum. Getting an early start costs five yards. Getting a late start—or starting late from jumping back onsides—gives the quarterback more time and stifles the momentum of a blitzing defender. Without this momentum, surprise means little.

Spacing

Spacing is more critical in area overload blitzes than other schemes because (in this example) the defense only uses one half of the field. If the defenders aren’t well spaced, one offensive player may be able to block two defensive players and the numbers advantage is negated.

But spacing is more than just separation. It is also about applying pressure evenly. Uneven pressure allows quarterbacks to roll away from the blitz or step up into the pocket. Pressure must come from all angles, particularly those away from the overloaded area of the field where one-on-one matchups are in play.

Coverage

A well-executed blitz also requires coverage. Pressure is useless if there is an easy outlet for the quarterback. The secondary must be in synergy with the rest of the rushing defenders to execute an area overload blitz.

Overloading one side of the offensive formation typically produces holes in the coverage. It is the responsibility of the secondary (and other defenders not blitzing) to close those holes. This is particularly important when a blitz is not well disguised.

So What Happened In 2008?

The Irish defense didn’t execute particularly well in 2008.

Early in the season blitzes were poorly disguised. Opposing offenses varied the snap count and disrupted the timing of the Irish defenders. Adjustments were made, and soft coverage in the secondary allowed for relatively easy gains even in the face of pressure (see San Diego State, Purdue). Giving a cushion on an all-out blitz on third and long is acceptable. Backing off seven or eight yards on first and 10 with an aggressive pass rush isn’t.

Spacing was also problematic, particularly coming off the edge and getting pressure from the interior defensive line. Sergio Brown and Harrison Smith frequently blitzed unimpeded only to take angles that were too wide or too shallow. Inside linebackers Brian Smith and Maurice Crum rushed the middle with little regard for lane assignments. And virtually no pressure was applied from interior defensive linemen.

The majority of blitzes featured one or two facets requisite to success, but not all three. The result was easy outlets for opposing quarterbacks.

Blitzing is high-risk, high-reward. Unless there is production in the form of sacks, turnovers, incompletions, etc., why gamble and potentially allow a big play? Only in the Hawaii game did everything seem to consistently mesh.

What Does This Mean For 2009?

If the Irish defense can’t get more production from their pass rush it may be in trouble. The unit’s unquestionable strength is the secondary. Tenuta’s best bet is to exercise that strength and apply pressure early and often. Notre Dame must win first down and force long down and distance situations that cater to a blitz-heavy scheme backed by a strong secondary.

Moreover, the weakness of the defense figures to be the front four. To date, youth and inexperience have limited the potential of an otherwise talented squad of defensive linemen. An aggressive scheme can mitigate this weakness, but only if execution is improved.

If the Blue & Gold game is any indication, the Irish should be able to bring pressure from the edge. This means the internal pass rush will be the key to success. Fall practice must be focused on improving the disguise, spacing and coverage of the blitzing schemes, as well as developing depth up front.

A year learning with Tenuta calling plays should help the former, co-defensive coordinator Corwin Brown seemed reluctant to fully embrace Tenuta’s philosophy in 2008. A few players will need to step-up to assist in the latter.